Coronavirus (COVID-19) Updates

For the latest COVID-19 information and updates from Qatar Foundation, please visit our Statements page

A Syrian family walks toward a new temporary camp for migrants and refugees in Lesbos, Greece. Image source: YARA NARDI, via REUTERS

Dr. Sophie Richter-Devroe, Associate Professor in the Master of Arts in Women, Society and Development at QF member Hamad Bin Khalifa University’s College of Humanities and Social Sciences, on how the tightening of EU migration and asylum law has a particular impact on young women.

Right at the start of our conversations Aida stressed her fear of the sea: “I would have much preferred to go via the land border in Evros,” she said. In the end, she took a small, crowded dinghy from the shores of Turkey to reach Chios, one of the Greek islands in the Aegean. From there, she continued to Athens, where we met in the summer of 2019.

Dr. Sophie Richter-Devroe.

At that time, Aida was in her mid-20s and had been on the move for four years, fleeing her home country Syria. Her journey took her across many borders, from Aleppo to Beirut, then back to Syria, then from Idlib to Turkey, where she was caught and sent back to Syria several times. And finally, after two failed attempts, she crossed the Aegean to Greece.

For most migrants Greece constitutes a passage; they don’t want to apply for asylum and stay there.”

Aida is one of the many Syrians who follow the route via Turkey and Greece to reach their ultimate destination: Central or Northern Europe. In 2018, the year Aida arrived on the Greek island of Chios, the EU received 85.575 applications for international protection from Syrians (EASO, 2018). 13.390 out of these were lodged in Greece (AIDA-GCR, 2018). These statistics, however, do not reflect the actual numbers of Syrians arriving and passing through Greece, which most probably exceeded 20,000 in 2018. Official, reliable numbers are hard to find, because for most migrants Greece constitutes a passage; they don’t want to apply for asylum and stay there. Aida, too, never lodged her asylum claim in Greece, preferring instead to remain undocumented, as this would facilitate the final part of her migration journey to Germany where she planned to reunite with her family.

Aida’s tactic to avoid registration and remain ‘irregular’ or ‘illegal’ in Greece is no exception. Most young female migrants do not claim asylum in Greece. This tactic leaves them more options to cross borders, reach their destination, and/or unite with their families. Their avoidance of registration highlights the gendered nature of the EU’s border and migration regime. It stems from several interconnected factors:

The Dublin Regulations, which still form the basis for the EU’s asylum, refugee and border regime, oblige asylum-seekers to register their asylum claim and stay in the first European country they enter until their papers for relocation or family reunification are processed. Only once an individual (in practice, predominantly male) has been granted asylum can they apply for family reunification, but only for their immediate relatives. This therefore implies a legalist transition from the extended family to the nuclear family and the individual subject.

For Aida, who had only her parents and siblings in Germany, the legal route was therefore closed.”

Once the lens shifts from the text to actual implementation of the law, possibilities of mobility across borders become even less. While family reunification previously included cases of brothers and sisters, or parents and their adult children, the law now is conservatively interpreted to cover only marital spouses, and parents and minors. Even in these cases, applications are regularly rejected or suspended. For Aida, who had only her parents and siblings in Germany, the legal route was therefore closed. She never registered her asylum claim in Greece, as this would have meant remaining stuck there, or being sent back. The existing paper trail of her asylum case registration and first entry to the EU in Chios would have allowed German officials to deport her back to Greece under the Dublin Regulations. It is therefore by not registering and through taking ‘irregular’ smuggling routes that migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers in fact feel they have some, or more, agency and security in navigating through the EU border regime.

The tightening of EU migration and asylum law is felt particularly by young adult female migrants, such as Aida. If they register in Greece, their best – if not only – chance, however slim, to ‘legally’ relocate is through marriage and then family reunification. Indeed, Aida also spoke about several marriage proposals she received from Syrian men who had already secured their asylum and residency in Germany. But she rejected entering into such engagements and preferred the ‘illegal’ route instead.

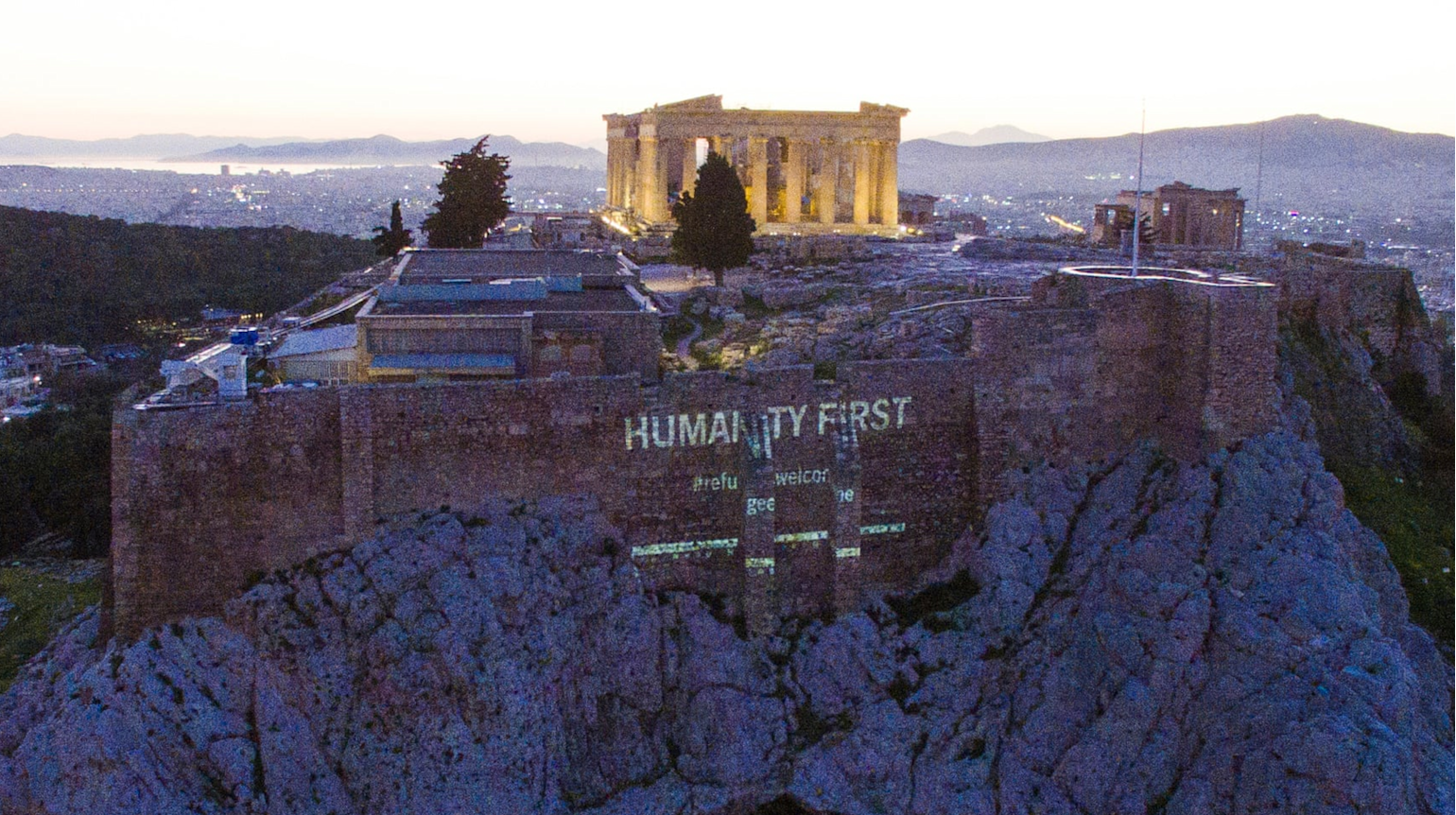

A ‘Refugees Welcome’ sign beamed onto the side of the Acropolis in Greece by Amnesty International in 2019, to draw attention to the plight of refugees trapped on Greek islands.

Indeed, marriage does not guarantee mobility across Europe’s tightly policed borders: I met several young Syrian women in Athens, some with young children, whose husbands were in Germany or other Central or Northern European countries. Even though they were eligible for family reunification, their applications either had been rejected or were on hold, leaving them in limbo stranded in Athens. In fact, many preferred to remain undocumented, just like Aida, and were waiting for a good moment to ‘illegally’ cross the borders to unite with their spouses. I also met several young women who had broken up their engagement or spoke of severe problems with their (future) husbands. Many had arranged their engagements or marriages hastily, sometimes not even having met their partner in person.

Marriage as a tactic for migration has complex gendered dynamics, and can put women at risk.”

Marriage as a tactic for migration has complex gendered dynamics, and can put women at risk. In order to comply with the law and qualify for family reunification, migrant women need to carefully, and sometimes strategically, employ family-making practices, such as marriage. This means keeping alive, and submitting to, potentially exploitative kin relations. Additionally, young female migrants must keep within set modesty codes to maintain or increase their marriage prospects.

Mobility – and immobility – across borders for young women like Aida is therefore regulated not only through EU migration and asylum law, but also through kinship structures and norms. Indeed, family structures and norms intersect with legal or illegal bordering systems, constructing a complex structural matrix of control that is particularly disadvantageous and precarious for young migrant women. Defined, both culturally and legally, as addenda to men, the supposedly ‘secular’, ‘rational’, ‘progressive’ and ‘gender-neutral’ EU migration law requires young women to cultivate potentially discriminatory kin relations. Laws and legal practices pertaining to asylum, citizenship and migration therefore work in tandem with conservative institutionalized kinship systems to form highly gendered border regimes.

-

Aida is a pseudonym to protect the research participant’s anonymity.

-

Dr. Sophie Richter-Devroe is Associate Professor in the Women, Society and Development Program at the College of Humanities and Social Science at Hamad Bin Khalifa University, and an Honorary Fellow at the European Centre for Palestine Studies at the University of Exeter, UK. Her broad research interests are in in the field of everyday politics and women's activism in the Middle East.

-

Her research is based on long-term ethnographic fieldwork in Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan and Greece. She has done research and published work on Palestinian and Iranian women’s activism, Palestinian refugees, Palestinian cultural production, Syrian refugees, and the oral histories of the Palestinian Bedouin in the Naqab. She is the author of "Women's Political Activism in Palestine: Peacebuilding, Resistance and Survival" (University of Illinois Press, 2018).